William John Evans, known as Bill Evans (August 16, 1929–September 15, 1980) was an American jazz pianist. His use of impressionist harmony, inventive interpretation of traditional jazz repertoire, and trademark rhythmically independent, "singing" melodic lines influenced a generation of pianists including: Chick Corea, Herbie Hancock, John Taylor, Steve Kuhn, Don Friedman, Marian McPartland, Denny Zeitlin, Bobo Stenson, Warren Bernhardt, Michel Petrucciani and Keith Jarrett, as well as many other musicians world-wide. The music of Bill Evans continues to inspire younger pianists like Fred Hersch, Bill Charlap, Lyle Mays, Eliane Elias and arguably Brad Mehldau, early in his career. He is considered by some to be the most influential post-World War II jazz pianist.

Evans is an inductee of the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame.

Bill Evans was born in Plainfield, New Jersey, United States, to a mother of Rusyn ancestry and a father of Welsh descent. He received his first musical training at his mother's church. Evans's mother was an amateur pianist with an interest in modern classical composers, and Evans began classical piano lessons at age six. He also became a proficient flautist by age 13 and could play the violin.

At age 12, Evans filled in for his older brother Harry in Buddy Valentino's band. At this age he was able to interpret classical music, but he couldn't improvise. In the beginning, he played exactly what was written in the sheet, but soon started trying to improvise, while learning about harmonies in the songs and how to alter them. Meanwhile, he was playing dance music (and jazz) at home. In the late 1940s, Evans played boogie woogie in various New York City clubs. He attended Southeastern Louisiana University on a music scholarship, and in 1950 performed Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto on his senior recital there, graduating with a degree in piano performance and teaching.

Evans's drug addiction most likely began during his stint with Miles Davis in the late 1950s. A heroin addict for much of his career, his health was generally poor, and his financial situation worse, for most of the 1960s. By the end of that decade, he appeared to have succeeded in overcoming his addiction to heroin. However, during the 1970s, cocaine use became a serious and ultimately fatal problem for Evans. His body finally gave out in September 1980, when — ravaged by psychoactive drugs, a perforated liver, and a lifelong battle with hepatitis — he died in New York City of a bleeding ulcer, cirrhosis of the liver, and bronchial pneumonia. Evans's friend Gene Lees bleakly summarized Evans's struggle with drugs to Peter Pettinger as "the longest suicide in history". At the time of his death, Evans was residing with his partner Laurie Verchomin, in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Bill Evans is buried at Roselawn Memorial Park and Mausoleum, Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana (Section #161, Plot K), next to his brother Harry Evans, who died the previous year. The inscription reads, "William John Evans; August 16, 1929; September 15, 1980".

Evans is an inductee of the Down Beat Jazz Hall of Fame.

Bill Evans was born in Plainfield, New Jersey, United States, to a mother of Rusyn ancestry and a father of Welsh descent. He received his first musical training at his mother's church. Evans's mother was an amateur pianist with an interest in modern classical composers, and Evans began classical piano lessons at age six. He also became a proficient flautist by age 13 and could play the violin.

At age 12, Evans filled in for his older brother Harry in Buddy Valentino's band. At this age he was able to interpret classical music, but he couldn't improvise. In the beginning, he played exactly what was written in the sheet, but soon started trying to improvise, while learning about harmonies in the songs and how to alter them. Meanwhile, he was playing dance music (and jazz) at home. In the late 1940s, Evans played boogie woogie in various New York City clubs. He attended Southeastern Louisiana University on a music scholarship, and in 1950 performed Beethoven's Third Piano Concerto on his senior recital there, graduating with a degree in piano performance and teaching.

Evans's drug addiction most likely began during his stint with Miles Davis in the late 1950s. A heroin addict for much of his career, his health was generally poor, and his financial situation worse, for most of the 1960s. By the end of that decade, he appeared to have succeeded in overcoming his addiction to heroin. However, during the 1970s, cocaine use became a serious and ultimately fatal problem for Evans. His body finally gave out in September 1980, when — ravaged by psychoactive drugs, a perforated liver, and a lifelong battle with hepatitis — he died in New York City of a bleeding ulcer, cirrhosis of the liver, and bronchial pneumonia. Evans's friend Gene Lees bleakly summarized Evans's struggle with drugs to Peter Pettinger as "the longest suicide in history". At the time of his death, Evans was residing with his partner Laurie Verchomin, in Fort Lee, New Jersey. Bill Evans is buried at Roselawn Memorial Park and Mausoleum, Baton Rouge, East Baton Rouge Parish, Louisiana (Section #161, Plot K), next to his brother Harry Evans, who died the previous year. The inscription reads, "William John Evans; August 16, 1929; September 15, 1980".

Bill Evans – New Jazz Conceptions 1956

01. I Love You

02. Five

03. I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good

04. Conception

05. Easy Living

06. Displacement

07. Speak Low

08. Waltz For Debby

09. Our Delight

10. My Romance

11. No Cover, No Minimum (Take 1)

12. No Cover, No Minimum

This groundbreaking recording was the first to feature then-unknown Bill Evans as a leader, and it also introduced a trio format of piano, bass, and drums, which would become Evans’s standard format for playing and recording. New Jazz Conceptions, recorded when Evans was just 26, merges his articulate, vigorous playing with the music of fellow Tony Scott Quartet musicians Teddy Kotick on bass and the extroverted Paul Motian on drums. The album’s four original compositions include “Five,” a witty, complicated song which makes clever use of the chords from “I Got Rhythm,” and the disjointed, slightly off-kilter “Displacement,” a study in a common Evans theme of playing against the meter and around the beat of a composition. The most remarkable material is the wonderfully eloquent piano solo, “Waltz for Debby,” written for Evans’s niece, which became perhaps the most renowned classic of his musical career.

02. Five

03. I Got It Bad and That Ain’t Good

04. Conception

05. Easy Living

06. Displacement

07. Speak Low

08. Waltz For Debby

09. Our Delight

10. My Romance

11. No Cover, No Minimum (Take 1)

12. No Cover, No Minimum

This groundbreaking recording was the first to feature then-unknown Bill Evans as a leader, and it also introduced a trio format of piano, bass, and drums, which would become Evans’s standard format for playing and recording. New Jazz Conceptions, recorded when Evans was just 26, merges his articulate, vigorous playing with the music of fellow Tony Scott Quartet musicians Teddy Kotick on bass and the extroverted Paul Motian on drums. The album’s four original compositions include “Five,” a witty, complicated song which makes clever use of the chords from “I Got Rhythm,” and the disjointed, slightly off-kilter “Displacement,” a study in a common Evans theme of playing against the meter and around the beat of a composition. The most remarkable material is the wonderfully eloquent piano solo, “Waltz for Debby,” written for Evans’s niece, which became perhaps the most renowned classic of his musical career.

Bill Evans Trio – Portrait In Jazz 1959

01. Come Rain Or Come Shine (Take 5)

02. Autumn Leaves

03. Witchcraft

04. When I Fall In Love

05. Peri’s Scope

06. What Is This Thing Called Love

07. Spring Is Here

08. Someday My Prince Will Come

09. Blue In Green (Take 3)

10. Come Rain Or Come Shine (Take 4)

11. Autumn Leaves (Take 9, Monaural)

12. Blue In Green (Take 1)

13. Blue In Green (Take 2)

Lyric and thoughtful, pianist Bill Evans proved an urbane bridge between the early bop style of Bud Powell and playful funk of Horace Silver, and the later, modern approach of pianists like Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett (indeed, Jarrett went as far as to record with Evans’s backup band of drummer Paul Motian and bassist Gary Peacock). Evans’s second album as a leader, Portrait In Jazz combines a pair of originals–”Blue in Green” and “Peri’s Scope”–with a handful of show tunes and standards, including a version of “Someday My Prince Will Come” that pre-dates Miles Davis’s adaptation. With a preference for irregular phrasing and a taste for unusual chord spellings, Evans was frequently able to recast old chestnuts and tired warhorses into new gems and spirited charges, as he does here with “Witchcraft,” “Spring Is Here,” and “When I Fall in Love.” And although he recorded in many different formats throughout his career, including duets with himself, the power and beauty of Evans’s trios helped him lay a special claim to that grouping.

02. Autumn Leaves

03. Witchcraft

04. When I Fall In Love

05. Peri’s Scope

06. What Is This Thing Called Love

07. Spring Is Here

08. Someday My Prince Will Come

09. Blue In Green (Take 3)

10. Come Rain Or Come Shine (Take 4)

11. Autumn Leaves (Take 9, Monaural)

12. Blue In Green (Take 1)

13. Blue In Green (Take 2)

Lyric and thoughtful, pianist Bill Evans proved an urbane bridge between the early bop style of Bud Powell and playful funk of Horace Silver, and the later, modern approach of pianists like Herbie Hancock, Chick Corea, and Keith Jarrett (indeed, Jarrett went as far as to record with Evans’s backup band of drummer Paul Motian and bassist Gary Peacock). Evans’s second album as a leader, Portrait In Jazz combines a pair of originals–”Blue in Green” and “Peri’s Scope”–with a handful of show tunes and standards, including a version of “Someday My Prince Will Come” that pre-dates Miles Davis’s adaptation. With a preference for irregular phrasing and a taste for unusual chord spellings, Evans was frequently able to recast old chestnuts and tired warhorses into new gems and spirited charges, as he does here with “Witchcraft,” “Spring Is Here,” and “When I Fall in Love.” And although he recorded in many different formats throughout his career, including duets with himself, the power and beauty of Evans’s trios helped him lay a special claim to that grouping.

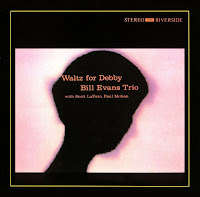

Bill Evans Trio – Waltz For Debby 1961

02. Waltz For Debby (Take 2)

03. Detour Ahead (Take 2)

04. My Romance (Take 1)

05. Some Other Time

06. Milestones

07. Porgy (I Loves You, Porgy)

08. Discussing Repertoire)

09. Waltz For Debby (Take 1)

10. Detour Ahead (Take 1)

11. My Romance (Take 29)

Recorded live at the Village Vanguard, this set rounded out what became known as an early “full” portrait of Bill Evans by following Sunday at the Village Vanguard with most of the rest of the music he played on June 25, 1961. Very little in the annals of piano-trio jazz ever reached the clarity of execution that Evans made his own with the recordings from this single date. With bassist Scott LaFaro and drummer Paul Motian, Evans reached a rapport that sounded whisper-intimate, rolling into gentle cascades and then rhythmically pouncing juts. On the keys, Evans sounds at once completely walled-off and nakedly open as he takes on “My Foolish Heart” and the title melody. The chords are voiced ever so oddly, as are the bass and drums. Coming as it did several months in the wake of the successful first episode in Evans’s Vanguard, Waltz for Debby just made it all the more obvious what a wonder the world had in this trio and its leader.

DOWNLOAD

The Bill Evans Trio – Moon Beams 1962

01. Re: Person I Knew

02. Polka Dots and Moonbeams

03. I Fall In Love Too Easily

04. Stairway To The Stars

05. If You Could See Me Now

06. It Might As Well Be Spring

07. In Love In Vain

08. Very Early

Moonbeams was the first recording Bill Evans made after the death of his musical right arm, bassist Scott LaFaro. Indeed, in LaFaro, Evans found a counterpart rather than a sideman, and the music they made together over four albums showed it. Bassist Chuck Israels from Cecil Taylor and Bud Powell’s bands took his place in the band with Evans and drummer Paul Motian and Evans recorded the only possible response to the loss of LaFaro — an album of ballads. The irony on this recording is that, despite material that was so natural for Evans to play, particularly with his trademark impressionistic sound collage style, is that other than as a sideman almost ten years before, he has never been more assertive than on Moonbeams. It is as if, with the death of LaFaro, Evans’ safety net was gone and he had to lead the trio alone. And he does first and foremost by abandoning the impressionism in favor of a more rhythmic and muscular approach to harmony. The set opens with an Evans original, “RE: Person I Knew,” a modal study that looks back to his days he spent with Miles Davis. There is perhaps the signature jazz rendition of “Stairway to the Stars,” with its loping yet halting melody line and solo that is heightened by Motian’s gorgeous brush accents in the bridge section. Other selections are so well paced and sequenced the record feels like a dream, with the lovely stuttering arpeggios that fall in “If You Could See Me Now,” and the cascading interplay between Evan’s chords and Israel’s punctuation in “It Might As Well Be Spring,” a tune Evans played for the rest of his life. The set concludes with a waltz in “Very Early,” that is played at that proper tempo with great taste and delicate elegance throughout, there is no temptation by the rhythm section to charge it up or to elongate the harmonic architecture by means of juggling intervals. Moonbeams was a startling return to the recording sphere and a major advancement in his development as a leader.

DOWNLOAD

No comments:

Post a Comment